Eureka

Stills

About

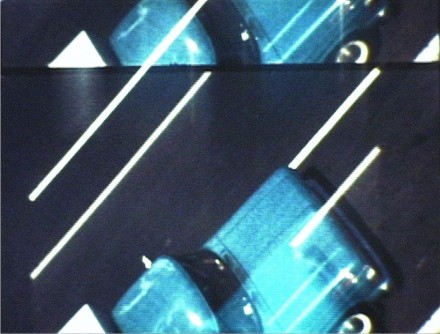

"Re-photography, superimposition, zooms, mathematically determined editing, and so on are not simply elements of style or 'techniques' in Gehr’s films. They become basic structuring devices, whose effects on the image and the viewer are interrogated by the film. We are forced to pay attention to them; we can not simply see through them to something else. Part of Gehr’s rich engagement with the earliest period of filmmaking at the turn of the century comes from his delight in an era in which audiences were amazed not simply at seeing a baby playing with its pabulum or a train arrive at a station, but at the very fact that such things were presented on a screen before them, had been filmed and were now projected. Films such as the early views shot by the Lumiere brothers capture a world, a time, and a place, but also the process of their transformation by the machinery of vision that had just been invented. It was the processing of reality through cinema that fascinated cinema’s first audiences and which Gehr asks us to rediscover. This double vision of a world and of its literal abstraction (taking it out of a specific time and space, preserved as a brief fragment on a bounded screen) by the cinema is something that Gehr achieves again. But to rediscover this primal experience of film’s relation to the world Gehr takes a long detour made necessary by our century-long familiarity with cinema which has rendered it invisible. For most filmmakers and film viewers film has become something one simply looks through in order to get at either a dramatic story or documentary evidence. Gehr discovers a world by making our sense of cinema and its transformation no longer automatic.

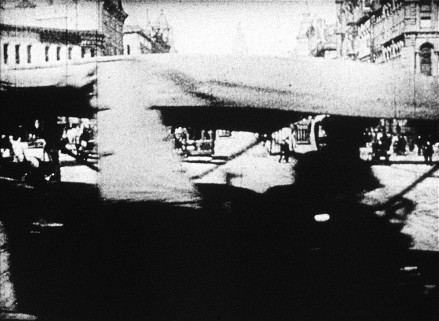

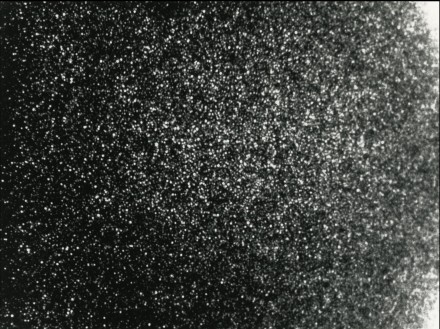

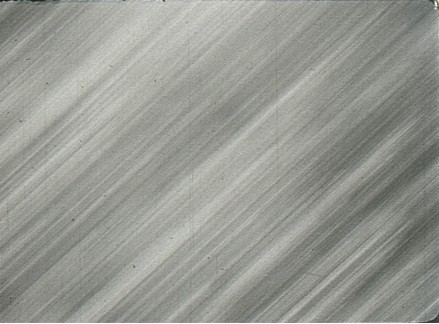

But the world does not simply bow out of this picture. Rather, we suddenly catch our act of seeing the world, of finding out place within it. In Eureka, for instance, Gehr did very little to the gem of early actuality filmmaking his had discovered. We still see a trip down Market Street on a sunny day around 1902 in San Francisco. But Gehr’s slowing down of the image, his refusal to clean it or cosmetically remove scratches or dirty particles from its surface, these small but significant decisions on Gehr’s part guarantee that we never just see the street, the day, the city; we are not allowed to simply become tourists of the past. Instead, we see the way the new invention of cinema interacted with the space of the street, the ways its frame voraciously swallowed up the everyday life of animals and people and the trajectories of vehicles. We sense not just a place, but the way space is transformed into place. We see both the rigid unswerving patterns of a major thoroughfare, the mechanical tracks of the trolley cars, the almost maniacal sense of using up space to get somewhere. And we also see the constant crisscrossing of that space, its sometime dangerous appropriation by people; men and women hurrying to destinations and boys ignoring and thwarting any such sense of purpose. Unrelentingly the camera bears down on a terminal, an anchoring point of urban architecture, a tourist spot and traffic axis. But the camera also discovers the accidental that crosses its path (Eureka!) and the wind that ruffles a man’s extraordinary beard. This is a film that not only documents a place in time, but a modern spatial vision, a look and technology that makes this street the sort of place it is. And here in this preserved piece of history, one also sees the chemical dance of film grain that makes up the material of Gehr’s own History. We do not simply see Market Street circa 1902, but a film of Market Street, and it is as fascinating as the site itself. Film may in some sense exist indifferent to emotions, objects, beings, or ideas. But early in his work Gehr realized that film, even conceived as a thing in itself, can never exist outside of history. The very dance of grain on the screen acquires a history of its production, its screenings, its viewings. History is the place no place can avoid.”

– Tom Gunning, “Placing the films of Ernie Gehr, Serene Intensity, The Films of Ernie Gehr, MOMI 1999

Films

-

Other films by this artist in our catalogue

- Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalMorning

Ernie Gehrcolor, silent, 5 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalWait

Ernie Gehrcolor, silent, 7 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalStill

Ernie Gehrcolor, sound, 54 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalReverberation

Ernie Gehrblack and white, sound on CD, 25 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalTransparency

Ernie Gehrcolor, silent, 11 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalField (Long Version)

Ernie GehrsilentRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalHistory

Ernie Gehrblack and white, silent, 15 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalSerene Velocity

Ernie Gehrcolor, silent, 23 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalField (Short Version)

Ernie Gehrblack and white, silent, 13 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalShift

Ernie Gehrcolor, sound, 9 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalBehind The Scenes

Ernie Gehrcolor, sound, 5 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalTable

Ernie Gehrcolor, silent, 16 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalUntitled

Ernie Gehrcolor, silent, 4 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalAlong Brighton Avenue (A.K.A Untitled: Part One, 1981)

Ernie Gehrcolor, silent, 30 min - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalMirage

Ernie Gehrcolor, silent, 12 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalSignal—Germany On The Air

Ernie Gehrcolor, sound, 37 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalRear Window

Ernie Gehrcolor, silent, 10 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalThis Side Of Paradise

Ernie Gehrblack and white, sound, 15 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalSide/Walk/Shuttle

Ernie Gehrcolor, sound, 41 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalFor Daniel

Ernie Gehrcolor, silent, 72 minRental format: 16mm - Read More

Passage

Ernie Gehr - Read More

Experimental

ExperimentalPrecarious Garden

Ernie Gehrcolor, silent, 13 minRental format: 16mm