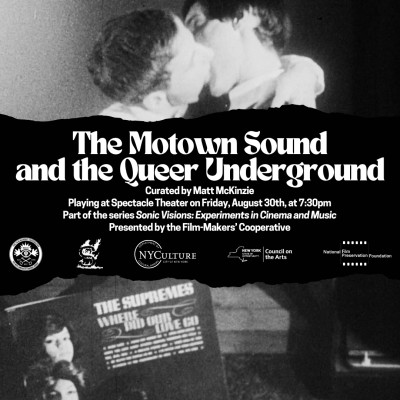

Screening

Join us at Spectacle Theater on Friday, August 30th, at 7:30pm, for five queer avant-garde shorts from the 1960s featuring the "Motown sound," curated by Matt McKinzie.

Program:

- Amphetamine, Warren Sonbert and Wendy Appel, 1966, 16mm-to-digital, black-and-white, sound, 10 minutes

- Where Did Our Love Go?, Warren Sonbert, 1966, 16mm-to-digital, color, sound, 15 minutes

- Behind Every Good Man…, Nikolai Ursin, 1966–7, 16mm, black-and-white, sound, 8 minutes

- Remembrance: A Portrait Study, Edward Owens, 1967, 16mm, color, sound, 6 minutes

- Lupe, José Rodríguez-Soltero, 1966, 16mm, color, sound, 49 minutes

Total Run Time: 88 minutes.

Program note by Matt McKinzie:

Experimental cinema and pop music have long been intertwined: look no further than Bruce Baillie’s use of Ella Fitzgerald’s debut single “All My Life” in his celebrated structural film of the same name, or the oeuvre of multimedia artist and “Father of the Music Video” Bruce Conner. Yet, the proclivity of queer experimental filmmakers to feature pop music in (or alongside) their work — especially in pre-Stonewall 1960s America — is particularly radical. Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising (1963) is a classic example. In that film, a group of Tom of Finland-esque bikers don their leathery garb to Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet,” foreshadowing the blend of pop music and homoeroticism Anger would conjure two years later in Kustom Kar Kommandos (1965) with the image of three young studs sensuously buffing a hot rod in a fuchsia dreamscape, underscored by the Paris Sisters’ cover of Bobby Darin’s “Dream Lover.” Four years after that, a myriad of midcentury mega-hits (e.g. Elvis Presley’s “I Got Stung,” the Shangri-Las’ “Leader of the Pack”) populated the soundtrack of John Waters’ otherwise silent feature-length debut Mondo Trasho (1969). An early Divine vehicle that set the transgressive tone for the Pope of Trash’s later work, Waters’ film was influenced by everything from Anger’s Hollywood Babylon to Andy Warhol’s homoerotic epic Sleep. (That film, when first shown in New York in 1964 — as a benefit for the Film-Makers’ Cooperative, no less — was soundtracked by a transistor radio playing Top 40 tunes). By juxtaposing outsider imagery with AM radio juggernauts made for (and consumed by) the masses, these filmmakers collapsed the mainstream and the underground into a beguiling audiovisual amalgamation and irrevocably transformed the meaning of each text in question. (Watch those bikers getting dressed in Scorpio Rising and tell me you don’t envisage a parallel universe where Vinton has dropped the “she”s and “her”s and swapped “blue velvet” for “blue denim”).

The Sixties were a sonically rich decade, regarded by many scholars and historians as the period when modern pop music was born. 1966–7 in particular is considered a banner year, with the release of now-legendary LPs like the Beach Boys’ baroque pop masterpiece Pet Sounds (1966), the Beatles’ psych-rock landmark Revolver (also 1966), and the Velvet Underground & Nico’s proto-punk self-titled debut (1967). Beyond these albums, a potpourri of musical movements and moments defined the decade — the British Invasion, Woodstock, the Greenwich Village folk revival, the troubadours of Laurel Canyon — though none more significant than the arrival of “the Motown sound.” A Detroit record company founded in 1959 and incorporated in 1960 by Berry Gordy Jr., Motown begat “an upbeat, often pop-influenced style of rhythm and blues associated with… numerous Black vocalists and vocal groups since the 1950s, characterized by compact, often danceable arrangements,” and played a major role in racial integration in popular music thanks to the crossover success of the label’s Black, predominantly all-women pop acts like the Supremes, the Marvelettes, and Martha Reeves and the Vandellas. Certainly a number of successful male stars came out of the Motown firmament (Marvin Gaye, Stevie Wonder, Smokey Robinson, to name a few). Yet, there is no denying the power and lasting legacy of the label’s girl groups who, in the words of Minnesota Public Radio’s Andrea Swensson, “turned the whole game around. [At Motown] a woman’s voice could deliver the lead as well as support it, harmonies locking together, a squad unified in power and voice… by the end of the decade, [the Supremes] would be Motown’s best-selling act, and will have paved the way for a long lineage of powerhouse trios like the Pointer Sisters, En Vogue and Destiny’s Child.”

Despite the cultural impact of Gordy’s label — particularly that of its women artists — its ‘60s output is rarely considered politically trenchant in the way other, overtly topical music of the era is. Wanda Rogers warbling about her “boyfriend so far away” and pleading, “Please Mister Postman, look and see / is there a letter, a letter for me?” (on 1961’s “Please Mister Postman”) or Diana Ross imploring listeners not to “hurry love / you’ll just have to wait / ‘cause love don’t come easy / it’s a game of give and take” (on 1966’s “You Can’t Hurry Love”) sounded milquetoast compared to Joan Baez’s soul-stirring rendition of “We Shall Overcome” at the 1963 March on Washington, or Janis Ian’s meditation on interracial love in 1967’s “Society’s Child,” or Jimi Hendrix’s ear-splitting and awe-inspiring desecration of the Star-Spangled Banner on the Woodstock stage at the height of the U.S.’ involvement in the Vietnam War.

Gordy’s apparent avoidance of politicized music changed in the ‘70s when he allowed Marvin Gaye to record and release What’s Going On (1971). A song cycle told from the perspective of a Vietnam War veteran returning home to the States and bearing witness to the country’s drug epidemic, rampant poverty, and ongoing generational divide, Gaye’s album became a cultural touchstone that outwardly subverted and transformed Motown’s reputation of “respectability” and apolitical musical palatability. Still, to consider Motown’s ‘60s period entirely apolitical (thereby demarcating the release of Gaye’s LP as the first instance Gordy infused his label’s music with a certain sociopolitical consciousness) is to overlook the less obvious (but equally legitimate) ways Motown — and in particular, its ‘60s girl groups — made a significant sociopolitical impact, and how Gordy’s “Sound of Young America” ethos was itself a political act in tandem with the broader youth counterculture of the time.

As Mark Clague, Professor of Musicology at the University of Michigan, writes in his essay What Went On: The (Pre-)History of Motown’s Politics at 45rpm:

Suzanne Smith [in her book Dancing in the Street: Motown and the Cultural Politics of Detroit] pushes Motown’s involvement with politics back to at least 1963 in her analysis of the company’s release of its first spoken word album—Martin Luther King’s speech for the Detroit Freedom March. Smith further identifies other issue songs in the Motown catalog that predate What’s Going On. In June 1966, for example, Motown released Stevie Wonder’s cover of Bob Dylan’s ‘Blowin’ in the Wind,’ and a complete album exploring the urban crisis, Wonder’s Down to Earth, appeared in the same year. Two years later, Gordy’s need for a hit for the Supremes helped create ‘Love Child,’ a message song that warns of premarital sex, unplanned pregnancy, and unwed motherhood.

Smith’s and Clague’s scholarship dispel Motown’s reputation of apoliticism during the ‘60s by highlighting songs and albums from its pre-What’s Going On period that deal directly with political concerns, yet live in the shadow of the “middle-of-the-road” and family-friendly fare the label is nowadays best known for. Still, by centering Black women vocalists and daring to carve out a racially-integrated space in a predominantly white pop music market, Motown’s “middle-of-the-road” fare proves quite progressive. The lyrics of a No. 1 hit like “Baby Love” might not have been groundbreaking, but the fact that Black women were alluringly, confidently singing them (and taking them to the top of the Billboard Pop Singles Chart) was.

Motown’s ‘60s catalog also cultivated an ethos of inclusivity, thereby uniquely touching the lives of marginalized folk — particularly people of color and members of the LGBTQ+ community. As Mary Wilson of the Supremes noted in a 2015 interview with Pride Source: “The music was inclusive. It didn’t matter who you were, the music touched your soul…. I’ve always said that Motown was an ambassador for love and for friendship because it brought people together.” Martha Reeves of Martha and the Vandellas commented in the same interview:

I think gay people came out of the closet mainly for racial reasons, because if you can accept somebody being gay then you can accept somebody being Black. Gay people fit right in with us. It was no big deal… ‘Dancing in the Street’ was to allow people to block the streets off with the police forces and yellow tape, come out of their house and dance without fear… it’s about freedom. It’s about being who you are, and being free to be who you are… That’s the freedom that we learned as Motown artists. That’s the way Motown was — free. The ‘Sound of Young America.’ And that’s everybody.

Marissa Lee of Mission Magazine illuminates the absence of gendered lyrics in many of the romantic ballads that came out of (and were influenced by) Motown in the ‘60s, making those ballads “unintentionally progressive”:

There’s an explicit gendering in the lyrics of most songs, making it an obtrusive fact that each song is dedicated to one gender and one gender only… it often goes unnoticed that the decadent soul songs [of Motown] …forfeited pronouns, instead opting for the ambiguous ‘baby’s’ and ‘honeys’ that populate their lyrics. This may not have been done on purpose, but it definitely served a purpose… We’re granted solace from binaries and… given more, perhaps unintentional, genderless expressions of adoration.

These “unintentionally progressive,” “genderless expressions of adoration” welcome a queer reinterpretation, or re-appropriation, of the “Motown sound.” Warren Sonbert — an early star filmmaker of the New American Cinema movement and later a pioneer of polyvalent montage — achieves exactly that in his debut film Amphetamine (1966), which opens this program. A collaboration with Wendy Appel (future member of the guerilla filmmaking collective TVTV), this 10-minute, black-and-white experimental short begins with a shot of the Supremes’ 1964 album Where Did Our Love Go? playing on a turntable. Over the sounds of that LP’s title track, “Baby Love,” and “I Hear a Symphony,” an intoxicating mélange of homoerotic images unfold: under chiaroscuro lighting, preppy young gay men lounge, canoodle shirtless, take intravenous drugs, and passionately kiss each other (the lattermost conveyed in a breathtaking, 360-degree shot modeled after the kiss scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo). Here, Motown’s best-selling group becomes the de facto Greek chorus of a euphoric night of gay passion, their reputation of “apoliticism” and acceptability complicated by the transgressive and liberating imagery with which the filmmakers have fused them. Diana Ross, Mary Wilson, and Florence Ballard’s sumptuous harmonizing seems to elucidate the chemical high the men on screen are experiencing. Sonbert and Appel’s visuals imbue that harmonizing with new, queerer meaning in return.

Sonbert’s follow-up Where Did Our Love Go? (1966) is titled after the Supremes’ song and album of the same name. In it, the young gay filmmaker follows his friends (many of them involved with Andy Warhol’s factory scene, and some of whom appeared in Amphetamine) around New York City: at gallery exhibitions, and in artist lofts, studios, and storefronts. His colorful images of camaraderie and creativity (including footage captured within Warhol’s studio) are accented by moments of eroticism and humor (a close-up of a painting of a nipple at an art show, for example) and accompanied, notably, by the Shirelles’ “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?”. The Shirelles were considered major forerunners and contemporaries of the girl groups that came out of Motown, and Sonbert flanks their classic number with a cluster of contemporaneous Motown-adjacent hits (namely the Ronettes’ “Be My Baby”; producer Phil Spector credited Berry Gordy and “the Motown sound” as an influence on his own “Wall of Sound” production). The result is a kind of extended music video in which Sonbert reflects the zeitgeist of his community and the times; a queer-coded love letter to friendship and the mid-‘60s downtown art scene, named for one of the Supremes’ biggest singles (and LPs) and enlivened by artists who both influenced and echoed the “Motown sound.” (It is also worth noting that Sonbert’s third film Hall of Mirrors — which does not appear in this program — is underscored by Jimmy Ruffin’s “What Becomes of the Brokenhearted,” a Billboard Top 10 single for Motown in 1966 that was later used in Jeff Scher’s 1995 tribute to Sonbert shot shortly before his death, simply titled Warren).

In Nikolai Ursin’s short documentary Behind Every Good Man… (shot between 1966–7) — which played in the 2023 program “Pride at the Film-Makers’ Cooperative” and later in Lucy Talbot Allen’s 2024 program “Portraits of Trans Lives c. 1970” (from the Film-Makers’ Cooperative’s series Films for Social Change, Revisited and Expanded) — an unnamed Black trans woman articulates her hopes, desires, and ambitions in voice-over, while embarking on daily activities (e.g. clothes shopping, going on a date, putting on makeup, setting her dinner table) to the sounds of Dionne Warwick’s “Reach Out for Me” and “Don’t Make Me Over.” While Warwick was not signed to the Motown label, she was a contemporary of Motown artists like the Supremes and similarly broke new ground for Black women in pop music in the mid-1960s. The film culminates with our protagonist putting on the Supremes’ “I’ll Turn to Stone” (from their 1967 album The Supremes Sing Holland-Dozier-Holland) and dancing around her living room. Behind Every Good Man… functions as both a “hopeful documentary [and] vital cultural document” in which the Supremes, and their friend Warwick, underscore a Black trans woman’s experiences of joy, agency, and self-affirmation over the course of a single day.

Ursin’s film is followed in this program by Edward Owens’ painterly 1967 evocation Remembrance: A Portrait Study. In this six-minute short, Owens — an early member of the New American Cinema Group and a protégé of both Gregory Markopoulos and Jonas Mekas — soundtracks dreamlike superimpositions of his mother and her friends conversing, laughing, and smoking cigarettes one evening with Dusty Springfield’s “All Cried Out.” (Springfield’s 1964 hit single “Wishin’ and Hopin’” also plays in Ursin’s Behind Every Good Man…). Springfield played a significant role in the dissemination of the “Motown sound” on both sides of the Atlantic. As noted by music scholar Annie Janeiro Randall:

Springfield was the most important figure in facilitating the Motown Invasion. In addition to covering many Motown hits herself, she gave the Supremes, Stevie Wonder, the Temptations, and many other groups their first television exposure in the UK. The Motown stars’ appearance on Springfield’s television special The Sounds of Motown in 1965 was as significant as the Beatles’ landmark 1965 appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show, which catapulted them into the commercial stratosphere. The Sounds of Motown was conceived and hosted by Springfield for the express purpose of igniting the careers of the Detroit singers in European markets. Through Springfield’s advocacy, these Detroit artists were transported into the Europop spotlight.

Springfield proves a Motown contemporary — and champion — whose similarly decadent, soul-and-R&B-influenced pop sound accentuates the reverence with which Owens, a queer Black filmmaker, has documented his mother and her friends. In a decade of mainstream American filmmaking oversaturated with depictions of suffering and subjugation experienced by Black people (think 1961’s A Raisin in the Sun, 1964’s Nothing But a Man, 1967’s Hurry Sundown), Owens adulatory depiction of the older Black women in his life — resting, pensive, donning jewels and furs, enjoying each other’s company — is as rare as it is radical.

The final film in the program, 1966’s Lupe, is a candy-coated “dime-store baroque” that tells the life story of Mexican movie star Lupe Vélez (originally titled Life, Death, and Assumption of Lupe Vélez) by gay Puerto Rican filmmaker José Rodríguez-Soltero. Created as a response to Kenneth Anger’s delineation of Vélez’s rise to fame and fall from grace in his book Hollywood Babylon, and produced contemporaneously with Andy Warhol’s film of the same name starring Edie Sedgwick, Lupe is one of only three films Rodríguez-Soltero made in his lifetime that are currently available. Like Owens, Rodríguez-Soltero is an overlooked early filmmaker of the New American Cinema and the queer avant-garde of the ‘60s; both filmmakers’ extant works have recently been restored and made available digitally by the Film-Makers’ Cooperative. While Rodríguez-Soltero does not shy away from the tragedy of Vélez’s life (complicated by drug use and struggles with mental illness), his filmic portrait is far from exploitative or lachrymose, focusing instead on the allure of Vélez’s celebrity and her eventual spiritual transcendence. As noted by Jesse Ataide of Queer Modernisms:

The emphasis is on magnetic star presence [and] the visuals, as the lusciously overripe, oversaturated colors evoke Technicolor melodramas of an earlier era warping [and] fading with the passage of time. The influence of fellow queer auteurs are unmistakable: Anger’s ironic pop music soundtracks, Jack Smith’s diva worship, Warhol’s cult of personality — but what distinguishes Lupe is how its subject is treated as something more than material to be mined for ironic camp parody or even affectionate retrospective recuperation… [the film] express[es] a genuine emotional investment in its subject not often found in this type of experimental cinema.

Rodríguez-Soltero’s “genuine emotional investment” is accompanied by a variegated soundtrack featuring Spanish flamenco, Cuban boleros, Elvis Presley, the Rolling Stones, and Vivaldi. Perhaps most memorable is the inclusion of Martha and the Vandellas’ Billboard Top 10 hit “I’m Ready for Love” and the Supremes’ smash single “You Keep Me Hangin’ On” played back-to-back during the film’s climax, which consists of a striptease performance followed by Lupe’s death from a barbiturate overdose and subsequent, gleeful ascension into the empyrean realm. The magnetism of these Motown earworms, coupled with Rodríguez-Soltero’s affectionate gaze, transmute the agony of Vélez’s experience into cinematic ecstasy.

In all of these films (made in 1966–7, the “banner year” for American pop music), the “Motown sound” underscores moments of joy, catharsis, pleasure, and/or transformation experienced by queer and trans folk — often queer, trans, and/or gender-nonconforming folks of color. This lineup thereby aims to complicate the reputation of sociopolitical neutrality associated with the “Motown sound” by presenting its significance in the lives and art of these marginalized communities, while affirming its place in the tradition of pop music in 1960s queer underground cinema at large.

Program note © Matt McKinzie.

Sources:

- “John Waters: On Stage with the Pope of Trash (Extended) | BFI,” British Film Institute, 4 November 2015.

- Randy Lewis, “1966 could be rock ‘n’ roll’s most revolutionary year, thanks to the Beatles, Dylan and the Beach Boys,” Los Angeles Times, 12 August 2016.

- “Motown.” Dictionary.com, n.d.

- “The 150 Greatest Albums Made By Women,” National Public Radio, 24 July 2017.

- Tyina Steptoe, “Marvin Gaye’s ‘What’s Going On’ Is as Relevant Today as It Was in 1971,” Smithsonian Magazine, 18 May 2021.

- Amanda LeClaire, “Motown’s Little-Known Political Hits Started Before Marvin Gaye,” Detroit Public Radio, 7 July 2020.

- Mark Clague, “What Went On?: The (Pre-)History of Motown’s Politics at 45rpm,” Michigan Quarterly Review, University of Michigan, Volume XLIX, Issue 4, Fall 2010.

- Chris Azzopardi, “Motown Icons Mary Wilson & Martha Reeves Talk Gay Followings, Supremes Reunion (Because Of Course),” Pride Source, 14 August 2023.

- Marissa Lee, “The Joyful Gender Neutrality of Motown,” Mission Magazine, n.d.

- Steve Huey. “The Shirelles.” AllMusic, n.d.

- “Footnote: ‘Answer’ songs were common in the 1960s. The Shirelles’ No. 1 single of ‘61, ‘Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow,’ for instance, inspired a response by Motown’s own Satintones, ‘Tomorrow and Always’.” From: “The Miracles – ‘Shop Around’.” Classic Motown. 2024.

- Jann S. Wenner. “Phil Spector: The Rolling Stone Interview.” Rolling Stone, 1 November 1969.

- Katie Hacala, “Berry Gordy and Phil Spector.” Motor City Media, 24 July 2014

- Maya Simone Cade, “Behind Every Good Man,” Black Film Archive, n.d.

- Annie Janeiro Randall. “Dusty Springfield and the Motown Invasion.” Institute for Studies in American Music, Vol. XXXV, Issue 1, Fall 2005, pp. 8-9.

- José Rodríguez-Soltero, “Lupe,” The Film-Makers’ Cooperative, n.d.

- Jesse Ataide. “Lupe.” Queer Modernisms, 10 June 2021.

*Part of our series SONIC VISIONS: EXPERIMENTS IN CINEMA AND MUSIC.